If you've followed the progression of my Care of Vintage posts, you will know that I'm writing these in anticipation of including the material in a book which I'm tentatively calling Getting Started With Vintage—a Modern Woman's Guide.

One of the best things about being this Modern Woman for whom I'm writing is the vast amount of information she can find online. In researching available texts, websites, and videos about basic mending, I have been bowled over with the quantity of really good information. Especially great for many of us are step-by-step video tutorials. I believe it is beyond the scope of my book to describe sewing techniques, but I am confident that, knowing what to look for, the beginning sewer can find what she needs to get started.

If you know how to sew, you are well on your way to being able to take care of the mending needs of your vintage finery. If you are already a seamstress, my best advice is to consider the way the garment was originally sewn in your repair work. Respect what has been done to the best of your ability and your work will blend in, even if this means (for instance) not using the newest gadgets on a modern sewing machine.

For those who don't know how to sew, or need a refresher, this section is about the most basic sewing skills that you may want to learn to do yourself. I know there is every kind of "modern woman" out there, and some will take off and fly with sewing, others will grimace at the very idea of threading a needle. For the reluctant, a seamstress can do these tasks for you. For the potential aviatrix, I have included some links to get you started.

Although it certainly is nice, you don't have to have a sewing machine to do basic mending. Equip yourself with a sewing kit for hand mending if you don’t already have one. Included should be spools of thread in basic colors, various hand sewing needle sizes (including sharp, fine needles to slip through silk and smooth rayon), beeswax to run your thread over to keep it from tangling, small thread-snipping scissors, a seam ripper, sharp pins, and a pin cushion. You will want to keep a collection of replacement fasteners including hooks and loops, and snaps in various sizes. You can scout for vintage sewing items at flea markets and yard sales, although many of these haven't changed significantly in 100 years or more, so new will do fine.

I would suggest you consider managing at least these mending jobs:

Resewing or replacing of loose or missing buttons and other fasteners

Restitching an open or loose seam

Bringing a snag to the inside of fabric

Removing pilling

Restitching a loose or missing hem

Closing up tiny holes in sweaters

Getting a sticky metal zipper to run smoothly

One online set of very clear tutorials for beginning hand sewers is monkeysee.com's "How to Sew by Hand" video series.

If you are a little farther along in your skills, you can add patching holes and mending tears, discreet mends in lace, and restoring missing beads and trims.

A Few Maintenance specifics

Photo by An Artsy Girl

Buttons. Vintage buttons are their own delight, with characteristic shapes and materials associated with different eras. I like to replace missing buttons from my vintage finds with similar vintage buttons. Sometimes that means changing out an entire set if I can’t find one close enough, so it is great to have a resource for sets of vintage buttons, whether that is a shop in your town, or an online shop. There are also some pretty convincing reproduction vintage buttons to be had these days. Monkeysee.com's "Sewing on Shirt Buttons" and "Sewing on Shank Buttons" should get you started with sewing the buttons on.

Buttonholes. Sometimes a buttonhole becomes frayed and needs repair. If you are ready to tackle this intermediate mend, you can find a very clear tutorial on craftsy.com, "How to Sew a Buttonhole by Hand."

Hems. There are three basic hem stitches, and again, it's nice to follow the style of the vintage hem you are mending. At megannielsen.com, there is a very good step-by-step tutorial for each of the hem stitches ("Hand Sewn Hems").

Photo by Hoyt Carter for the Vintage Fashion Guild Fabric Resource

Pills. Those little fluff balls that accumulate on sweaters and fabrics with any nap are pretty easy to remove from wool, but not so easy when the pilling is on a synthetic fabric such as polyester. I keep both a pumice sweater block and sharp safety razor for de-pilling. The sweater block is great for wool and helps with synthetics, but a carefully wielded razor can get the more “sticky” pilling off. There are also fabric shavers with screens that are designed for various types of fabrics.

Pulls. For pulling a snag or snagging a pull, I use a Knit Picker. This inexpensive little gadget hooks a snag in a knit with ease, and pulls it to the inside of the fabric.

Seams. If you are sewing by hand, the sturdy and flexible backstitch is the way to go. Besides the monkeysee.com tutorial "Sewing - The Back Stitch" there's threadsmagazine.com's "How to Master the Backstitch."

Snaps, and hooks and eyes. Again, those great monkeysee.com basic sewing videos include "Sewing on Snaps" and "Sewing on Hooks and Eyes".

Sweater holes. If they are very small, you can discreetly mend a hole with matching thread, embroidery floss, or yarn. I like the tutorial over at tashamillergriffith.com ("How to Fix a Small Hole in a Knit").

Zippers. Because I’m deep into vintage clothing, I have a large collection of vintage metal zippers for replacing broken ones. Make sure to replace, or have a seamstress replace, a broken vintage zipper with a similar vintage model. If that's not possible (say, because you can't put your hands on a similar enough zipper), a modern zipper is acceptable. This may well not matter to you, but I'd caution you that a zipper of the wrong type can slightly lower the value of a vintage item. Also, and maybe it's just me, but I think there's a good feeling in having the right zipper, even if it's hidden. Using a sewing machine to put in a zipper is not beginning material, but using your trusty backstitch can repair a short stretch of loose stitching along a zipper.

A metal zipper missing one tooth is not necessarily ruined. If the zipper still runs smoothly, don’t worry about that tooth, it may never need attention.

If a zipper pull is “derailed”—slipped off one side of its tracks—you can sometimes get it back on track. [see my tutorial here].

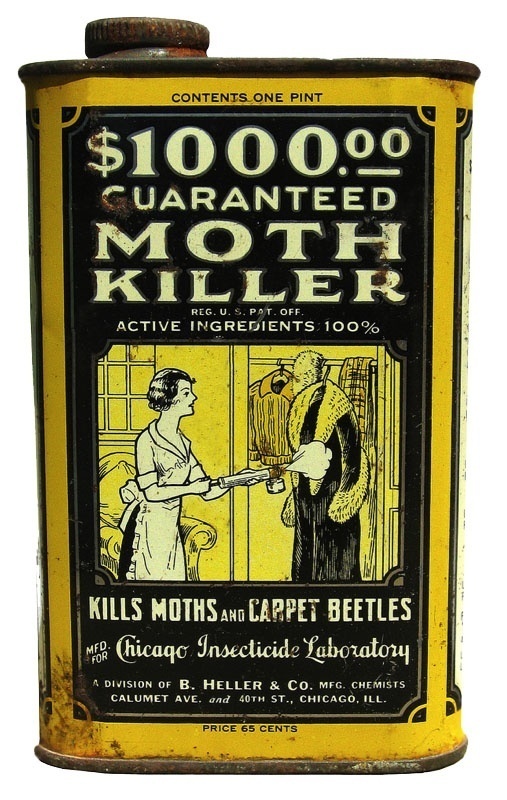

A slow or sticky metal zipper can be waxed by running a candle over the teeth (both beeswax and soap also work). A stuck vintage zipper can sometimes be budged by pushing on the teeth with a thick needle. You can also carefully dab the stuck section with a cotton swab soaked in WD-40. Once you have it going, launder out the WD-40 if possible, and then lightly wax the zipper with a candle.

When your cat and you had a fabric-ripping tussle, a moth ate your best sweater for lunch, or you stepped through the hem of your best gown, it's hard to imagine how a vintage favorite will ever be wearable again, but don't despair, many flaws can be discreetly fixed or camouflaged by a skilled seamstress, if not you. Refusing to give up on a great garment is a very vintage virtue. You've heard the expression make do and mend? It dates from WWII, when rationing and shortages were par for the course, but in our time, with limited resources and an awareness of the impact mass consumption has on the planet, doesn't making do and mending seem sensible?

If you’d like to see all my vintage care tips in one place, you might like my book Wear Vintage Now! Choose It, Care for It, Style It Your Way, available now!